Many Possible Lives

Season 7 Episode 3 | 26m 5sVideo has Closed Captions

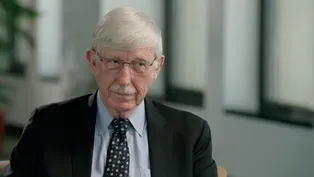

Kelly speaks with Dr. Collins, former director of the National Institutes of Health.

Kelly speaks with Dr. Francis Collins, former director of the National Institutes of Health, who oversaw the prominent Human Genome Project. Dr. Collins shares how genetics are most often misunderstood, his concern about the impacts of social media on adolescents, and what scientists know makes a lasting difference when it comes to our well-being.

Many Possible Lives

Season 7 Episode 3 | 26m 5sVideo has Closed Captions

Kelly speaks with Dr. Francis Collins, former director of the National Institutes of Health, who oversaw the prominent Human Genome Project. Dr. Collins shares how genetics are most often misunderstood, his concern about the impacts of social media on adolescents, and what scientists know makes a lasting difference when it comes to our well-being.

How to Watch Tell Me More with Kelly Corrigan

Tell Me More with Kelly Corrigan is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipWelcome to "Tell Me More."

I'm Kelly Corrigan.

I'm a writer, a podcaster, and a mom.

This season, number 7, is unlike anything you've seen from us before, because everyone who works on this show is reading the same headlines.

There is so much unsettling news about how people are actually feeling, so we have recruited the best scientists and researchers to separate fact from fiction and surface a set of practices we can all live by.

Join us for a 10-part conversation on wellness.

How do you get it and how do you keep it?

♪ Certainly, early childhood is just a critical time for laying down the epigenome and also laying down certain habits that are gonna be lifelong.

Corrigan, voice-over: This is Dr. Francis Collins.

You know him.

He was the longest-serving director of the NIH, spanning 12 years and 3 presidents.

He also led a team of scientists who, two years early and $400 million under budget, mapped the human genome.

So you led the phenomenally complex project of mapping the human genome.

I did.

When they first offered you the job, were you gung ho or terrified?

[Chuckling] I was terrified.

Yeah.

I was running a research lab at the University of Michigan.

I was pretty happy teaching medical students, taking care of patients, and having a lab that was pursuing all kinds of interesting projects on genetic disease, and the idea of walking away from all that--[sighs]-- to take on a-- oh, my God, government job--heh!-- which is what was gonna be necessary to come to the National Institutes of Health and stand at the helm of a project that about half the scientific community was opposed to-- Really?

Oh, yeah.

People have forgotten that.

Some of it was just disbelief that it was technically possible.

Mm-hmm.

When we started the Genome Project, you would be doing a pretty good thing if you read out a hundred letters of the DNA code in one day.

To get the whole thing done, we ultimately had to sequence a thousand letters of the code--[chuckling]-- every minute, 7 days a week, 24 hours a day.

The scale-up was breathtaking.

And the challenge there is twofold.

It's getting people to believe in this possibility... Yeah.

and managing across continents.

Was there any doubt that it would change the world?

No, I don't think, if you thought about the consequence of having a reference copy of our own instruction book, you could say, "Oh, this isn't gonna matter."

There were some people saying, "Well, you know, we will never "figure out how it works anyway, so it'll be fine to say we did it, but it won't change anything."

Well, they were wrong.

Mm-hmm.

Heh heh!

It's transformed all of those things, although it didn't happen overnight.

Once you have those 3 billion letters in front of you, you still have to figure out how to read them.

Yeah, and so what is a transformation that could have only come on the heels of you mapping the genome?

Take what we've learned about cancer.

After all, cancer is a disease of the genome.

It happens because you have a misspelling in a critical gene somewhere in a cell, somewhere in your body, and that misspelling tells that cell, "It's OK to just keep growing and don't stop," and then a tumor results.

The idea that you could actually read out that entire instruction book in a cancer cell in the space of a day or two and then say to this patient, "This is why your cancer is growing, here is the list of possible drugs that we might use," now we can pick the one that we believe is gonna be the best for you.

This is precision medicine, precision cancer therapy.

We never could have done that without genomics to get us there.

I'm the beneficiary of that, so, as a 36-year-old with two kids in diapers and was diagnosed with a 7-centimeter tumor, very specific understanding... Mm-hmm.

of what was going on and therefore how to treat it.

There you go.

You're a great-- And here I am, 20 years later, clean.

You are a great example.

Yeah.

We've already reduced cancer deaths about 25% in the last 20 years, and a lot of that is because of genomics.

So how might that also affect people who are suffering from mental health disorders?

Mental health disorders are clearly involving genetics as well as environment, but let me just say it's really complicated.

I know, I know.

We're learning that from everyone.

Yeah.

All you scientist people can't wait to tell us how complicated it all is.

Ha ha ha ha!

It's good to be reminded.

Well, maybe we shouldn't be surprised it's complicated... Yeah.

'cause it involves the brain.

The brain that you and I have between our ears is the most complicated structure in the known universe.

86 billion neurons in between your ears there, each of which has, on the average, about a thousand connections.

It's breathtaking.

It is.

But it must also involve incredible, subtle complexities that we are on the track towards trying to understand, but when you consider what we still don't know about the normal function of the brain and how all those neurons work together, it's getting in the way of being able to understand precisely what's wrong...

Right.

when something isn't working the way you want it to.

We are getting there.

I mean, we know oodles more than we did 10 or 20 years ago about mental health, but unfortunately, we're not at that sort of revolutionary moment where now we can say, "I get it, I understand it."

What will the next 10 or 20 years bring?

Especially with AI, you know, you think about, like, "Is this complex, miraculous thing"... Yeah.

"capable of understanding this complex, miraculous thing?"

There are people wondering about that, but AI is only as good as how you've trained it.

Mm-hmm.

We don't have enough data to feed the machine learning system so that it can come up with those brilliant insights that we're counting on.

Mm-hmm.

But we're going to get that data, so let me tell you about the brain initiative.

OK. And which now involves hundreds of neuroscientists and engineers and robotics experts and AI experts who are trying really to figure out, how does the brain normally work?

Already, they have gone through the process of beginning to take a full census of what are all the cells in the brain?

And we are now good enough with single-cell biology to look at a single cell and ask it, "What are you doing?

Mm-hmm.

"What genes do you have "turned on, and which ones are turned off, and which neurotransmitters are you responding to?"

Now, you also want to know not just what's one cell doing, but what are the circuits doing that involve thousands, millions of cells that are responsible for a certain activity?

Like, I just moved my hand.

How did that happen?

How did I lay down a memory and how do I retrieve it?

Will it also help us understand better why some genes express and others don't?

Yes.

That's a whole area of intense investigation.

You could call that epigenomics.

Mm-hmm.

The signals that tell which genes to turn off and which ones to turn on are emerging in great proliferation.

Now, that's what my own lab works on in the case of diabetes, trying to understand how do those subtle changes in which genes are on or off create normal circumstance like insulin and glucose doing what they're supposed to... Sure.

or how does that get out of whack?

The fact that genes and environment play a critical role in mental health is pretty obvious in sort of general ways, but it's always good to sort of have an example where you've really nailed it down, so let me tell you one.

OK.

There's a particular gene called monoamine oxidase that's expressed in the brain, and it has a lot to do with neurotransmitters and whether they're present in the right quantities at the right time, and it turns out there is a version of that gene that doesn't work quite as well.

It's not knocked out.

It's just sort of knocked down.

OK.

If you have that, especially if you're a male, your likelihood of having some antisocial behavior as an adult and ending up in some trouble with the law goes up, not hugely.

So people started to look carefully at that, like, "OK, what else is involved?"

And it turned out it was childhood trauma that made the difference.

If you had that version of the gene, and you'd had childhood trauma of a significant sort-- child abuse, violence-- your likelihood of ending up in a difficult circumstance with the law goes way up.

But if you had that same gene, that same risk, and you'd not had that experience in childhood, you were relatively a lot less likely to have that kind of outcome.

So, other example, this is a puzzle, but I think it's pretty profoundly important.

Alzheimer's disease... Hmm.

a disease that everybody is really worried about, but you know what?

The strongest prevention of Alzheimer's disease, in terms of environment, it's your education... Hmm.

that you did back when you were in your teens and your 20s.

If you graduated high school, went to college, got a college degree, your risk of Alzheimer's goes substantially down.

Now, isn't that weird?

Yeah, and that's been isolated?

Yeah.

Huh.

What I think that says is that during that time, your brain is still developing-- you haven't finished that till you're about 25-- there's something you're doing in the educational process that's actually strengthening your circuits so that, when that risk of Alzheimer's starts to kick in, it doesn't kick in as easily.

Are there genes that indicate a higher risk for suicidality?

There are, in fact, dozens of genes that are involved in conditions like schizophrenia or depression or autism... Mm-hmm.

or obsessive compulsive disorder.

And we kind of know where they are, but by a very large-scale study, where you have thousands of people with the condition and thousands of people who don't, and you scan the entire genome and you say, "Is there anything different here?

[Chuckles] And you find, oh, over here, the people that had a T in that position have, like, a 5% higher likelihood... Mm-hmm.

of having that disease than the people who had a C. Mm-hmm.

But that 5% is a pretty tiny effect.

Right.

And it isn't gonna be very useful clinically.

Yeah, I feel like I want a behavioral psychologist at every table... Ha ha ha!

to sort of filter it through everything they know about our nature and our behavior patterns that are most predictable or common.

Yeah.

I heard you say to Judy Woodruff once that you sort of regretted that the NIH didn't do more research into behavior.

Hmm.

I do think there's so much we don't understand about how health behaviors are chosen, and if we really want to improve people's lifespan and health span, that a lot of that's gonna be making good decisions about nutrition and exercise and sleep and all the rest.

And yet, we are really woefully unclear... Mm-hmm.

about how best to inspire the kind of health behaviors that we think people should be taking.

So we have some episodes coming up about what we think of as, like, the big 4 drivers of mental health: sleep, nutrition, exercise, and connection.

Mm-hmm.

Are there genes that make it more likely that we will enjoy vegetables, love breaking a sweat, be risk-takers socially such that we might develop deeper relationships...?

Yes, but they're gonna be these genes that have this tiny little individual effect.

Mm-hmm.

And gathering together can have somebody sort of tilted more in the direction of being an exercise lover or somebody who really doesn't want to do that stuff.

You know how everyone's talking about, um, how things get transferred from one generation to another?

Mm-hmm.

What should we understand about that?

It's a bit of a controversial topic.

It is.

[Chuckles] I brought it to you for a reason, Francis Collins.

Ha ha ha!

OK. Let me try not to screw it up.

Ha ha ha!

So, the epigenome...

Yes.

this--which is a really important concept, is what are all the things that affect how that DNA, the genome, functions in a given person, in a given cell, a given organ.

Yes.

Is there any sort of lingering echo of something that happened to that parent that now is transmitted to the child?

And particularly, could that even go on for several generations?

There are a few examples, [chuckles] instances, for instance, where individuals suffered really severe environmental deprivation, famine, where you can sort of look and see that maybe the third generation is having more problems with glucose and diabetes than you would have expected.

So there's an inference there that maybe the epigenome can have some multigenerational effects, but it's pretty subtle.

Pretty much, you get to start over when that genome passes through the germline and starts a new person.

Of course, it carries all those variants with it... Sure.

that might carry certain risks of illness.

I mean, that's how it is that disease runs in families, but that's actually written into those letters of the DNA code.

That's the A, C, G, and T. The epigenome, sort of the next layer on top of that, mostly seems to go away when you pass on to the next generation.

And that layer is what laypeople call nurture?

Ah!

Nurture.

I mean, is this where the conversation begins between your genes and your earliest environments and your earliest relationships?

Yes, so we shouldn't think of the genome as oblivious to the environment.

Yeah.

It's not.

I love the example of what musical training... Hmm.

does to the brain, because it's dramatic and you can actually see it.

So, if you're somebody who had intense musical training before the age of 7, as I did, and you image that person's brain as an adult, you can see a difference.

That part of their acoustic cortex that responds to musical sound has actually gotten a little larger.

That's the epigenome, must be doing that.

We don't quite understand that, but somehow, those incoming acoustic stimuli are telling neurons there, "Hey, we need more of you."

Which is so crazy... Heh!

that there's something happening, an idea is being presented to a young person, and it's changing their biology, it's changing something measurable and observable.

It totally celebrates growth mindset.

Absolutely.

Of course, to be honest, you have to think about the negative side of it, too.

Plasticity may mean that other kinds of environmental influences that aren't good for you are leaving their marks as well.

Of course.

Social media, for instance, comes to mind.

Do you have thoughts about how that might be impacting mental health?

There's a lot of work being done to try to understand the social-media effect.

It can be a positive connector of people to information and to each other, but I'm deeply concerned, particularly for young people, in the data that's emerged and that seems to be accelerating since about 2012, which is when social media, particularly Instagram, became so widely accessible and so heavily used... Mm-hmm.

by adolescents, particularly girls.

I don't think kids under 13 really ought to be having access to social-media platforms like Instagram.

When you're in a very vulnerable part, where your frontal cortex is still developing and all of this that's happening in an adolescence, which is complicated enough, and then you pile this on, it's deeply disturbing, sort of the most significant mental-health crisis for adolescents that's ever been recorded.

I hope, again, this is more of a wake-up call for the adults in society... Mm-hmm.

to say, "Wait a minute.

"If your daughter is facing a risk "that's gonna cause her likelihood "of becoming suicidal to go up significantly, you probably want to do something about that."

Well, that's what we are talking about.

So can't we actually put together that kind of realization across parent groups, across schools, without requiring a legislative solution which will immediately become a big political battle?

Yeah.

It's interesting.

I think about parenting all the time.

I have a 20-year-old and a-22-year-old, and I am so empathetic to all of us who are looking for answers about why our children are the way we are, and how much of it is driven by our parenting choices over the years.

Do you have thoughts about the ways that we might misunderstand or misapply genetics and nurture... Hmm.

to reflect on our own parenting influence?

Certainly, early childhood is just a critical time for laying down the epigenome and also laying down certain habits that are gonna be lifelong.

I think the greatest mistake people can make is to say, "Well, it's all hardwired, and so you're just gonna get what you get."

Right.

And, uh-- What could I have done?

Right, and the second-greatest mistake is to say none of it's hardwired.

[Chuckles] The ideal, then, is to try to recognize those and figure out how to nurture and shape those.

One of the things that came up in our last episode, which was about nurture... Mm-hmm.

was that we really need to keep art in the curriculum.

Yes.

Do you have thoughts about that?

Boy, do I ever.

[Both laugh] Saw a recent study trying to figure out, how do kids get caught into drug-use patterns?

So they're following more than 10,000 kids, starting at age 9 and going on to age 20.

They got all kinds of data on these kids.

And they're gonna track 'em for 10 years or something?

Wow.

Yeah, yep.

But already, you can start to see things developing because they already have 3 or 4 years of follow-up.

So, for instance, a child who has had exposure to a musical instrument turns out to have significant, better language development than a child that has not.

From that, and from many other studies, I think you could say musical training, if you want a child to have the best chance at language development, it should be in there, but it's not now.

And I'm involved in a project that NIH started called Music as Medicine, which is also about how we can use music therapeutically in adults.

And maybe for well-being.

And for well-being.

Well, sure.

We have lots of studies now.

People with chronic pain.

Mm-hmm.

Music as a non-pill approach can be very powerful.

People with PTSD, lots of studies there to show how that can be beneficial.

And we're just beginning to scratch the surface about how to take the music therapy that we've been doing since World War II, particularly for PTSD, and combining it with neuroscience to make it even more powerful.

Mm-hmm.

I think about-- I had to be in the choir in middle school.

You were forced to?

And I loved singing with my friends.

Heh!

Yeah?

It was, like, a class that we took during the day.

I know people now who, as adults, have signed up for choir because they feel like it's imbuing their life with something that they miss.

I just saw a study of adults who were invited either to sort of follow their usual practices of social interaction or to join a choir for 12 weeks, and then they studied these people who were in the choir versus those who weren't.

Oh, and there was one other arm of people who were just taught to sing, but by themselves... Uh-huh.

and with a coach, so it's the group thing versus the individual thing.

Many of them were people, um, who had chronic difficulties with pain.

Their pain sensitivity went measurably down... Huh.

and--heh!-- they also were found to have higher levels of oxytocin, which is one of those hormones that makes you feel good.

Yeah.

All that from group singing.

Do you think that there's diagnostic inflation around mental health?

Do you think that we're identifying each other casually or in doctors' offices... Heh!

naming conditions that--too quickly?

We're certainly diagnosing more people with mental conditions, especially kids in adolescence, than we did 20 or 30 years ago.

Is that because we were under-diagnosing then...

Right.

or we're over-diagnosing now?

Right.

I think the real question is, well, has it helped?

Has it improved people's functioning and flourishing to be able to actually name something that needs an intervention?

Clearly, in the past, there was a lot of stigma associated with anything that sounded like mental health or mental illness.

I think we still have quite a bit of that, but not quite as much... Yep.

so that's part of the way the door has opened, and I think that's good because a lot of those people really have benefited from it.

I worry, though, about a circumstance where there is a tendency, perhaps, not just to make a diagnosis, but to offer a pill to somebody who may or may not actually need that kind of intervention over the long term.

And once you start, and once the label's been attached, it's sort of harder to step away from it.

I feel like we as a nation learned a lot about how clever Big Pharma is with the oxycodone.

Hmm, mm-hmm.

Is there anything happening at the federal level that might protect us from something like that happening again, where mental health's concerned?

Think, at the federal level, particularly, the National Institute of Mental Health has a very broad portfolio of research, trying very rigorously to assess what's the right balance here.

You don't want to under-treat people... Sure.

who desperately need an intervention.

At the same time, if that's just being put there as sort of a Band-Aid on what could have been managed much more effectively with, perhaps, cognitive behavioral therapy-- Mm-hmm.

a very successful approach to a lot of these conditions, but not widely enough available for what the benefit might be-- then we got to do something about that, so yeah.

There's a lot of concern, a lot of attention, um, but, of course, have to say, having had the privilege of leading the NIH for 12 years, I kept bumping into the fact that we could do this great research and we can come up with this compelling conclusion, but then getting that to actually find its way into everyday clinical care and change practice oftentimes took 20 years.

Mm-hmm.

How frustrating.

[Chuckles] It's our system.

So can you help us understand how to recognize, like, great science... Mm-hmm.

and how to distinguish it from kind of a flashy headline that could be easily misunderstood?

[Chuckles] Please?

Ha ha ha ha!

Well, first of all, it's really critical to say what source are you looking at when you're seeing this flashy headline?

Is this, in fact, a well-established, journalistic source that's been around a while, or is this something that just popped up in Facebook from somebody who's quoting an anecdote and trying to tell you that answers everything?

And then, OK, what are they actually referring to?

Is this a research study?

Is it published?

Is it published in a peer-reviewed journal, which means other experts have looked at it and believe the conclusions are legitimate?

That's a good place to start, and then, OK, watch the language.

Anything that sounds really hyperbolic, [chuckles] be very careful about.

You want something a little more sober.

That's where the headlines get to be a problem, because the journalists will all tell you they write the story and then somebody else writes the headline.

Whoever that somebody else is, we never get told, and their goal is to get eyeballs to look at this story, and so it always sort of takes the level of excitement-- Ratchet it up.

Ratchets it up a bit.

Now, let's be clear.

Science is a work in progress.

Yes.

And so that story you read today in a peer-reviewed journal that seemed to have all the right criteria and had an interesting conclusion may be disproved...

Right.

next month or next year, and that's OK. That's the way it's supposed to be.

Yeah.

What you can say is that science is self-correcting.

There really is such a thing as truth.

That maybe is not so popular these days.

Boy, let's underline that.

Heh!

Yeah.

Stop here, everyone.

[Chuckles] Yeah, especially for a scientist.

You couldn't be a scientist if you didn't believe that there is objective truth to be discovered, and our goal as good detectives is to try to figure out what it is.

Yeah.

And sometimes we get false clues and we make mistakes and we go down a blind alley, but ultimately, we know there is an answer, and if we do everything right and other people help us along, we're gonna get that answer.

Yeah.

And then we add to that constitution of knowledge, and that builds the case for people having a better chance of achieving health.

Heh!

I loved being with you.

Thank you so much for your time and your work.

Oh, Kelly, it's great fun.

Kelly: Here are my takeaways from my conversation with Francis.

Number 1...

Number 2...

Number 3...

Number 4: Feeling low?

Join a choir.

Number 5... kids under 13 years old should not have access to social media.

And finally, number 6... And science is the only way to get us there.

If you'd like us to send you this list, we're happy to do it.

Just send an email to PBS@kellycorrigan.com.

[Theme music playing] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Dr. Collins points out how to distinguish reputable news from misinformation. (2m 37s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship