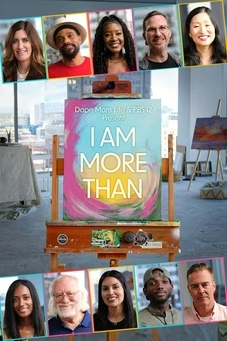

Decode Colorado

Homelessness

Special | 45m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

Learn about the history, current, and future state of homelessness in Denver.

Meet community resource experts, people who were formerly unhoused, and city officials who decode the history, current, and future state of homelessness in Denver. The second episode in the Decode Colorado series explores the systems currently in place that help, yet sometimes perpetuate, the unhoused crisis in our city, while hearing first hand stories of the challenges facing the unhoused.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Decode Colorado is a local public television program presented by PBS12

Decode Colorado

Homelessness

Special | 45m 2sVideo has Closed Captions

Meet community resource experts, people who were formerly unhoused, and city officials who decode the history, current, and future state of homelessness in Denver. The second episode in the Decode Colorado series explores the systems currently in place that help, yet sometimes perpetuate, the unhoused crisis in our city, while hearing first hand stories of the challenges facing the unhoused.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Decode Colorado

Decode Colorado is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

[Music] - Hey, lady.

How are you?

I'm doing okay.

Nice day.

[Laughs] All right, so here's my tent.

Obviously, Odin has done some things to it.

Odin.

Odin.

You okay?

Sit.

Do you want to peek in?

Do you want me to go in or?

The tents are Eskimo tents, and they're actually for ice fishing, I believe.

So, they have a thermal quality to them and they stay pretty warm, but, I mean, Denver's cold.

I have a power box where all my cords go into, my chargers, all that.

This is where Odin congregates.

[Laughs] He's spoiled.

He's even got toys.

[Laughs] That's the divider.

Let me turn around for you so you can see.

Yeah, I've got kind of inspirational things on here.

Lots of things I find, I will put them on here.

It is my inspiration board.

It's what I focus on when I need, you know, pick me up.

When I'm feeling down and I'm in this tent, I'll go and I'll read things, and then I'll remember why I'm here, what I've been through, and where I'm going, and then I feel better.

My daughter's names.

Oftentimes, I will dance in this tent like I have music playing.

There's a mirror on the other side, and I will dance it out.

I love dancing, I love music.

I'll stand at the mirror and do my hair.

Find clothes to put on.

- What's up?

- I have my dog.

Odin loves to dance.

He loves music.

We'll knock things over in here and make noise.

Neighbors will hear me yelling at him all day and all night, arguing.

We have a domestic relationship.

[Laughs] It's weird, but when you're in a tent by yourself, you can-- I mean, obviously, you can hear your neighbors, but it you can hear them very clearly.

Oftentimes, I've sat in here listening to people cry.

I've cried with them.

You hear people going through things.

That's why I say it's not just, "Oh, they're on drugs or they just-- No.

People are here or out there because they're hurting, they're going through things, and they don't have the right support or don't know what to do to get that.

Even set up as good as this tent is.

It this tent was outside that fence there and I didn't have my community to support me, what good is it?

It would be no good to me.

It definitely has-- It's home.

It's definitely home.

Yeah.

[Laughs] [Music] [Music] - Over the last decade in Colorado, housing prices have gone up much faster than incomes, and certainly much faster than incomes for people on social security, or those who are disabled, those working at entry level jobs.

- Three in ten Coloradans are housing unstable.

not everyone who is housing unstable ends up on the streets or visibly homeless, as we might say, but they are also unhoused.

- We have decided as a country, as a community, that it is not okay for people to starve to death and go hungry in our community.

We have not decided that about housing.

- Homelessness is not a choice.

It really is the fallout from several systems failing all at once.

It comes down to criminal justice, child welfare, education, and other systems that really have within them systemic and structural racism.

- When the criminal justice system discharge people to the streets with no resource, the mental health system discharging people from the mental health institutes, again, without housing and resources, when we see a continuing discrimination against people because of who they are, those are the things that create homelessness.

- For decades income has lagged the cost of living in this nation.

People who are less likely to be higher wage earners to exist comfortably in our society are people of color, women and people of color.

Income, and wages are tied at inextricably to someone's ability to care for themselves and keep shelter over their heads.

- We have seen gentrification happen right here in Denver.

Generations of families that have lived in these areas are being displaced and pushed out of their homes.

If people who grew up in the neighborhood could no longer stay there, that means that grandparents are no longer living near their grandkids, and that means that people are getting pushed out and may never be able to buy.

So where are they going?

They're going to the suburbs or going to other states, and yeah, some folks are going to the streets.

- We work with lots and lots of youth coming out of the foster care system.

That makes up about 38% of who we work with.

Young African-American men are three times more likely to experience homelessness than their white peer.

About 75% of the people experiencing homelessness are people you don't see.

They're people staying in shelters, or transitional housing, or other places where they are experiencing homelessness.

On the other hand, the 25% that you do tend to see are the people that have maybe some more chronic challenges or barriers, such as substance use and mental health disorders.

Particularly in the family homelessness, we see a lot of female heads of household where they are escaping domestic violence or some sort of other family breakup and just do not have the resources to be able to survive in our housing market alone.

- People assume that they've done something wrong or they would not be homeless.

The primary difference really is the availability of a support system.

I could experience domestic violence like any other mom.

If I lost my job, if I became ill, if I was evicted for whatever reason, I have a family that would take me in.

Most of the families that we see do not have those support systems available to them.

- We can't talk about homelessness without talking about trauma, and there are a lot of different traumas that happen.

For veterans, it tends to be things like PTSD and other things directly related to their service.

- They get home.

It's difficult to make things work because they've not been able to maybe deal with what they've seen and done.

- Having to pay a large percentage of their income towards rent, and then having something like a car breakdown or a medical bill that they need to take care of.

Not being able to access the services that they need, like not actually being able to navigate the institutions where they might be able to provide resources, and so they end up on the streets.

- All set.

- Set and ready.

- What was life like before you experienced homelessness?

[Music] - My life before I experienced homelessness, I mean, starting from childhood, I thought was pretty normal.

And then, went to the military.

Reality hit then a little.

I started self-medicating.

Got out of the military.

I was owning and operating a business, then the pandemic hit, had a string of unfortunate events kind of happened.

My vehicle was stolen with all my tools in it on a project, and that was the only vehicle I had at the time, and then got evicted due to that as well.

That's when I experienced homelessness.

Being a veteran and what I thought was a leader in my community, it was kind of hard to reach out to certain people or anyone at all.

So, going from owning a business to not having anything.

I mean, that was a reality check from hell.

I mean, all my life, 45 years old, I've never been homeless.

I've always provided, I've always been a go-getter, and then when you get to the moment of being safe and secure financially, thinking that, and within 30 days, losing everything you have, watch what savings you have dwindle to nothing, walking down the street with a suitcase was probably the most humbling and torturous event that I've experienced in my whole life.

So much so, it caused me to want to take my own life.

The first night I was homeless was the first night it snowed in Denver, and I slept under a bridge in Lakewood.

I was in the military.

One of the things I salvaged was a military sleeping bag so I could sleep in -20-degree weather, but that's all I had.

That's all I had.

I probably cried half of 24 hours I sat there.

Just a month and a half of walking the streets to kind of find out these resources and find out what's available.

It's very humbling to have to go into a Planet Fitness or somewhere just take a shower when you used to go there to work out.

You sit there and say, "Okay well, there's resources here.

A, B, C, or D locations.

"” Well, how are you going to get there?

Take everything out of your pockets, just carry your ID with you, and let's say, I want you to get to the west side of Denver from the east side of Denver.

No phone, no anything, not from the area.

Ready, set, go.

I mean, that reality was every day.

I lived that every day.

It was hard.

It's hard to get anything.

I mean, you could wait a month just to get a driver's license.

Depression has sank in deeply.

I'm self-medicating previous to this process, you know, and there's no amount of self-medication I can do at this point to numb where I'm at.

I was seeking, you know, some kind of medical treatment for anxiety and depression at the time, some psychological help, even talking to a therapist.

I knew I needed something because I couldn't sleep.

You know, I was always anxious, I was super depressed, I'd cry.

I needed some kind of medication to kind of bring me stable because of the situation I was in at the time, and I wasn't getting that.

That was my breaking point is when I tried to take my life by overdosing that weekend.

So, that's exactly what I did.

Because I couldn't get any help, I was like, you know, I'm not living another day like this.

I paid for hotel room.

That was I was a Friday night, did all that I could, passed out.

[Music] - To some extent, homelessness has always been with us.

You can read the Jack Kerouac books on the road and description of people living on the streets, in flophouses on Larimer Square back in the 50s and 60s, but modern-day homeless really became expansive in the mid-1980s.

Those who used to be in state mental health hospitals were moved to the community with a promise of there being adequate resources to provide care, and support for them, and housing in the community.

Most of those plans were not fully resourced and did not provide adequate housing and services.

The federal government pulled back on its investment in affordable housing, something that had grown in the 60s and 70s.

Those two things combined created this lack of fixed housing for people to live in, and more people then ending up on the street.

- That then was really built on by the economic conditions that we saw, you know, particularly in the 2000s, where family homelessness began to rise.

- When you look at our system of laws around housing or even our public engagement processes, they are really driven to the benefit of those with the greatest resources and land ownership interests.

We need to think about that different.

How do we drive our systems towards an equitable outcome?

We have to dismantle some of the racist systems that have given us the same result over and over.

- Schools are funded based on property tax.

So, when we talk about segregation, segregation was not just about keeping black and white folks separated, but it was also about where the resources for the tax dollars were going into those communities.

Redlining is actually directly correlated to folks experiencing homelessness, intentionally separating, keeping communities apart from one another.

And then, we come back and look at gentrification where these homes, these communities, these black communities have been intentionally uninvested in.

And then, you have these communities that have been deemed blighted by your government and folks are coming in saying, "Hey, I can give you this amount of money for your property.

"” And you're like, "That's the most money I've ever seen in my life.

"” You have new folks coming in.

You're then seeing the government actually invest in those communities where you're seeing businesses pop-up, you're seeing coffee shops, and yoga studios, bars, and restaurants.

And I'm not saying that those aren't beneficial, but those aren't beneficial for the community that has been historically disinvested in.

And so, we talked about gentrification.

That's what happens when you don't plan for the people that are currently in that neighborhood, when you're planning for what the future of that neighborhood looks like, and it becomes unaffordable to the folks that have held it down in that community when it was blighted.

- One of the things that we heard is we created the Department of Housing stability was how much people were concerned about where would their kids live?

Where would their grandkids live in Denver?

That the neighborhoods that they had lived in and had been able to afford were suddenly unaffordable.

How do we keep people in their homes they're already in and in the neighborhoods of their choice here in Denver?

We want to see people move when they want to move, not when they feel they have to move because of economic forces.

- We're seeing a real rise in the number of families that are staying in their vehicles.

We've seen exponential growth in the number of families experiencing homelessness as a result of Covid.

And during the pandemic, for the first time, we saw one of those families that were maybe one paycheck away from experiencing homelessness actually slip into not having a place to live.

- And at the same time, housing was skyrocketing.

Denver's a nice place to live and all of our inventory started again to go up and up on what had already been a decade of up.

- It was unprecedented what this community went through and what the providers in this community went through to try to make sure to continue to provide services.

The families that we serve and the veterans that we serve because our community are often times in larger groups and the contagion was greater.

We had to do some pretty major things in our community to try to continue to serve people.

Put many feet between beds that maybe had been closer together in that mass shelter and congregate shelter.

Our family motel, we used half of it specifically for those people who had been diagnosed with Covid.

- It is very hard to get healthy if you don't have a stable housing environment.

If you're living in your car, living on the street, and you are discharged to those environments, it is not conducive to healing.

- Unless we're addressing both healthcare and housing together, we're not likely to make a long-term difference in the lives of people experiencing homelessness.

We're likely to see people housed, and then ending up back on the streets.

[Music] - When I try to reframe it around what has been the benefit of Covid is I think, as a community, there were some light bulbs that went off around, like there's a stay-at-home order, and all of a sudden, people had to be like, "Oh wait.

We're telling people without homes to stay somewhere.

That doesn't make any sense."

- We know that your zip code and you're race determines your health care outcomes.

I am a young person whose family is a lot of medical professionals.

My mom was an OB/GYN, my brother's an anesthesiologist, and my cousin is a cardiologist.

My dad was a respiratory therapist.

Despite all of that, I have asthma.

This could have been prevented, but our ZIP code and our race has much more of a determination on what our health outcomes are going to be, even than our healthcare access.

My inhaler, my medication I take for my asthma is five thousand dollars a month.

Why not prevent that in the first place?

I wasn't born with asthma.

I got it because of environmental pollutants, you know, in our neighborhoods and the communities that we grow up in, and we know it's much higher in communities of color.

All of that is tied into the root causes of things like being unhoused, being incarcerated.

It's not being able to build generational wealth.

- We've been advocating housing is healthcare for probably 30 years, particularly those who are most vulnerable, those who have chronic health conditions, who have mental health issues, addictions, or those who are recovering from trauma.

Trauma is so prevalent, both in early childhood trauma that often leads to homelessness as well as the trauma of homelessness itself.

Colorado ranks near the bottom of all states in terms of its investment in behavioral health, and mental health, and addiction treatment, and that is starting to show.

The ability to get them connected to those long-term residential treatment services that they need is very difficult.

- There are about 40 million American adults who struggle with mental health issues.

There's about 20 million American adults that struggle with substance misuse, and yet most are housed.

It is totally possible to have supports and systems to be housed and have those struggles.

The biggest difference between what we're experiencing here in Denver versus someone in rural West Virginia with the same struggles is that rent in rural West Virginia is in the hundreds of dollars, and here in Denver, it is thousands and thousands.

- All right.

This is Cuica Montoya's interview.

Take one.

- I go by Cuica, but it's actually Cuicatl, which is an Aztec word from the Nahuatl language, which means song.

I'm going to reclaim it one of these days.

- I'm excited when you do.

And can you tell me a little bit about your adult life before you experienced homelessness?

- Yeah, absolutely.

So, I really worked really hard to build kind of a solid life.

Met my daughter's father in our early 20s, and you know, we had this kind of like suburbia life.

We were both grinding on our careers.

I worked in commercial real estate.

Getting up, taking my daughter to daycare, going to work, coming home, being a family.

Alcohol kind of had been a part of my life for a while, but it wasn't necessarily something detrimental.

When my daughter's father left me, it was like my world came crashing down, not only in my financial situation, but also in my mental health, kind of feelings of worthlessness, like I could make it work.

I kind of had two interventions on the same day, uncoordinated.

My family separately and my work separately on the same day.

If that gives you an idea of how hot of a mess I was.

So, they gave me an opportunity to go to treatment, but in treatment, I also was around other people who use drugs, and I was introduced to somebody who used meth.

Instead of staying with treatment, I went on a deeper, darker journey, and I ended up getting fired from my career of seven years.

That led to bouncing around from couch to couch, which eventually led me into literal homelessness.

When I started experiencing homelessness, reeling from the loss of my family and my financial stability increased kind of some of these coping strategies that weren't a problem before, and I was drowning myself in them after experiencing this traumatic event.

So, like, if you can think about experiencing homelessness for three years, if that's how I felt in the beginning, then you compound it day in and day out.

Also adding in kind of nobody wants to look at you when you're experiencing homelessness.

You know, I don't want to look at you.

I don't want to talk to you.

I don't want you to ask me for money, you know.

I don't even want you outside of my place of business.

All of that compounds an already-- Gosh, I'm getting a little emotional-- experience of feeling alone.

I went farther down than I had ever even imagined myself possible.

I started bouncing in and out of the criminal justice system.

I would say during one of my jail visits, I had to just get clean cold turkey, and then when I kind of got a little bit of my bearings around me, I remember looking around the jail and going, "This is not what I wanted for my life."

- We keep seeing this evolution and change of who's experiencing homelessness, really expanding to families, young people, the aging population.

It can happen to anyone at this point, particularly in our region because of the high cost of living.

In metro Denver, a two-bedroom housing wage is sixty seven thousand dollars a year.

So, in order to not be housing burdened, a household has to make sixty seven thousand dollars a year.

When we just had a minimum wage raised to $15 an hour and we're celebrating that, the reality is that's still not a housing wage.

And so, again, what we see is people not being able to afford to live here, and then you have things like healthcare, higher education, childcare, all of these rising costs that are just not keeping pace with our wages.

- People who have ties to this community don't necessarily decide that they want to move to the Eastern Plains or another state where it might be more affordable to live.

They have their family, their friends, and maybe grew up here.

It's just heartbreaking, actually, how many landlords end up raising rents to the point where the family literally has to leave, and many, many, many of the families that we serve, in particular, over the last 3, 4 years are suffering as a result of increased rents.

- We see investors buying apartment buildings, slapping a coat of paint on the walls, and jacking up the rent by 50 or 75 percent.

More and more people are competing for those limited slots, and that means that there are a few winners, more losers, and therefore more people sleeping on the streets.

The mayor's office estimates we have a shortage of 25,000 units of housing that's affordable to households below 30 percent of the area median income, and that's the threshold of the very, very low income population.

The city has plans of creating about five to six thousand units of housing over the next five years.

Well, even if they achieve that, that still leaves 19,000 people without the ability to find affordable housing.

Since there is such a shortage, the people who have the greatest resource, the greatest ability to compete for that are most likely to find and obtain that housing, and the folks with the most challenges, those who are mentally ill, have addictions, or coming out of the criminal justice system, those who are escaping domestic violence, they're not likely to be able to find and compete for that limited supply of affordable housing.

- I recently had someone who was looking for housing.

There were 30 some applicants for that one unit.

If you have a criminal record, it's very, very difficult to be the one that's ultimately chosen for that unit.

So, you have criminal justice, you then have things like the child welfare system.

- We are doing a good job of getting people off the streets, and young people into housing, and all of that, but we are not turning off the spigot, and so the inflow is massive.

One out of three foster care youth become homeless on the day they turn 18.

- Were you ready to live on your own when you were 18?

Are your children ready to live alone?

And, you know, did you have a family system that created a safety net for you?

Did you have a community, whether that was your synagogue, or your church, or your mosques, or school, or your college, or your doctor, or your mentor, did you have those things?

And you think about foster care youth.

Oh, cool.

Do you have trauma?

Do you have lack of relationships?

Have you lived in congregate settings for 15 years?

You should go live on your own.

Like, that's just not real, and we set expectations that aren't based in experience.

- Many children experience a bout of homelessness with their family.

They don't know where they're going to be tonight.

They don't know where they're going to be tomorrow.

They don't have a room of their own.

They don't know if they'll ever have a room of their own.

Those kind of things cause trauma, a great deal of trauma among children and their ability to do well in school and be in a stable school.

All of those things, If we can deal with this issue of family homelessness, I think that it would benefit so many children and their futures, and I really, really believe that we can do this for all populations, but families in particular.

- What we as a community often talked about in trauma is like well, what's wrong with you?

You must have done something to get here, or you didn't do enough, or this.

One of the things that's jargon and working with at-risk populations is trauma informed care.

I think the best way to break down what that means is not what's wrong with you, but what happened to you?

And then, as we think about populations, we need to be thinking that about humans, and we need to have that really one to one conversation that is about how do we support folks and say what happened to you?

That is a way more powerful question than what's wrong with you or what's your trauma?

- Raven, take two.

I really start to dig into spiritual meanings behind animals and try to feed into those qualities and apply them to my life to help myself.

The raven was the one that I identified with the most and that I saw the most out in the open in nature, and it's just beautiful creature.

So, there you go.

It's the Raven, and I think it fits.

My dog's name is Odin.

Odin is Thor's father.

He's a Norse god.

I am from Louisville, Kentucky.

I traveled here with my sister.

She's a nurse, and she thought it'd be a good idea to start our lives over in Denver, so hopped up here.

Before I ended up homeless, I really had, I guess, a typical one.

I worked at UC Health as a surgery scheduler.

I have a medical background.

My sister, she decided to move back to Kentucky, and I opted to stay here because things were going so well for me here.

I met someone, and he basically manipulated me through my emotions because I have a tendency to over care, I guess.

I lost my job, we ran out of money, and then he got us evicted out of there.

It wasn't out of money, it was just him being reckless and dumb.

Every opportunity I had, he would screw it up for me.

I blame myself because I had just left a toxic situation in Kentucky with my husband, so it's more like, you know better than this.

How dare you let another man bring you down like this.

To be real, I think I just kind of just gave up on myself.

I miss my kids and all that.

I just kind of fell into it, but I have a very strong mind and I just kept telling myself that I was not going to let this beat me.

I have two little girls in Kentucky, who I've been preaching to all these years about being strong and independent.

If I do that, then I'm just telling them to give up on everything they've ever done.

So, what I did was I made sure Odin and I were always in a safe location, where it was always well lit.

You have to have to keep your eyes open.

You can't sleep.

Can not sleep.

You sleep 10 minutes tops.

Odin is always why I got any sleep at all because he could watch me while I slept.

you fall asleep, you will get robbed, raped.

Anything happens.

At one point, we were sleeping at Arapahoe train station, and Odin, I had him tied around my waist as always.

He's like right in front of me.

There's this guy that just walked up while I was dozing off.

He sat next to me, and I don't know how he did it, but he sat next to me without Odin even knowing, and he just started touching me.

When I jumped up, Odin jumped up, and then we kind of like had an altercation.

Nothing bad.

I mean, no one got injured anything like that.

The guy just ran off.

After that happened, I didn't sleep no more just because I was just that determined to stay alive.

I was like, "Nope, not gonna let nobody catch me slipping.

Nope"” Odin I were walking up and down Federal.

No destination.

It's hot.

There was a guy.

He saw, Odin.

Odin attracts attention.

"Can I please pet your dog?

"” "Yeah.

He loves people.

"” He's loving on Odin, and Odin's loving on him, and he just starts crying.

I used to have a dog.

Long story short.

He loves animals.

He asked me if I was homeless.

I'm like, "Yeah.

"” We're just cruising, we're okay.

I wasn't really looking charity.

Just whatever.

He was like, "Follow me.

Let me show you something.

"” Obviously, I was scared because I didn't know this guy, I don't know anyone here.

I don't know what's gonna happen, but I had to take a chance.

So, he went to the camp.

I'm like, "I saw this here, but how does it work?

"” I never even heard of it.

He went inside and he went got the staff.

They came-- Not just the staff, the residents, they came out.

Miss Sherry, she's not here anymore.

She got an apartment.

Thank God.

I remember her specifically.

She reminds me of my aunt back home.

She came out and she gave me a hug.

This woman never met me before in my life.

I don't even know how she knew I needed a hug.

I hadn't had a hug since my sister left.

Not a real hug, you know.

She came out, she gave you me hug and she said, "Welcome.

"” I'm sorry.

When she said that, it felt like God was saying, "You made it.

It's gonna be okay.

You made it."

- Everyone has a right to housing and a right to healthcare.

We need to remove whatever barriers are preventing them from accessing it.

- Solving homelessness is complex.

It took us decades to get here, it's going to take us a while to get out of this.

First of all, we have to understand who's experiencing homelessness in real time so that we know what the need is in our region.

What we saw in January of 2022 is a little over 6800 people were experiencing homelessness on a given night.

Point in time is meant to be a snapshot of data that's opposed to what we see over the course of a year, which is over 28,000 unique Individuals experiencing homelessness.

One of the challenges we see in this country is that the data being reported to the federal government and to congress is a one-night snapshot, and that's how we're being resourced.

However, the actual need over the course of a year tends to be five times more than what is being reported.

- The model that we use that's most successful in getting people housed is called Rapid Rehousing to house people as rapidly as possible in the community where they want to live in a system with the rent for up to two years and provide services to them, support services, case management, and other services that they might need to make sure the children get into their school that they're going to be in, in the home that they're going to live in as quickly as possible.

My administration's created the first housing homelessness resolution fund to have the city have an ongoing effort to work to partner with those who are building and those who are maintaining housing in our city.

So, we've changed the way our shelters operate.

You know, when we came in, shelters had a certain amount of hours that they operate in.

Our shelters are open 24 hours, seven days a week.

- Making a welcoming place for all and a safe place for all is absolutely paramount in what we do.

So, our security team, those 18 security officers, they're trained in an outreach first type of approach.

So, they have a book of all of the resources that are available in the City and County of Denver.

So, as they are working with individuals and come across individuals who are in crisis, that is the first line of conversation.

In addition, we've just added crisis intervention workers to that team.

So, we are truly engaging individuals on a very human scale basis every day.

- But ultimately, being stable, being stabilized is what changes lives, and that's why we did things like our social impact bond program.

Right now, 325 souls or families are sheltered in that facility.

Stabilized, but also intensive services there be to help them, whether it's mental health, substance misuse disorder, whatever may be causing the challenge or pain barriers, they're in that facility.

It's one of the models that I'm most proud of.

- Built for Zero is really a national change movement.

They help communities create a response to homelessness that is really mired in data.

So, understanding by name who's experiencing homelessness, what their needs are, and not having, again, a one-night snapshot, but we like to call it a movie of who's experiencing homelessness.

And so, we've started with veterans here in metro Denver.

There are about 500 veterans experiencing homelessness, which we know them by name, who they are, what their needs are.

We're matching them to resources and making sure that we can move them towards stability.

We have decreased veteran homelessness by 31 percent in the last two years, and the national average was 11%.

- Every time it rains, it floods, and all you do is curse the rain, the likelihood is the next time it rains, it's going to flood.

Similarly, if you'd all you do is curse the homeless and you don't invest in the infrastructure of creating the housing and the health care needed to end homelessness, the likelihood is you're going to get the same over and over again.

- Prevention is the key.

Housing is the answer.

If someone is already in housing, to keep them in that housing is much less expensive, much less traumatic for the adults, and especially for the children, The veterans that we serve if they don't fall into homelessness in the first place.

If you're driving down the street or you're walking down the street and you see a camp you don't like or someone on the corner, it makes you uncomfortable.

I'm not suggesting you have to go in and be like, "Hey, let me fix your problems and what's happening,"” but don't turn away and don't empower the people around you to turn away.

- One of the things I always say is you can start by using person first language.

It's one of the most low barrier things people could do.

So, instead of saying homeless people, use person-first language, people experiencing homelessness.

- We are talking about humans, and when we turn away and we don't see people, they live in an invisible space, it is very dangerous and dark.

- I never thought I'd take my life, but then waking up from making that attempt was like, "Well, God has me here for a different reason or different purpose.

"” Somehow gained some type of courage to put my shirt back on, and lace what shoes I had on up, and go back to the resources I knew that were there, and give it another try.

Going through the life experiences I did, being homeless, I rebranded to Reed's Restoration and Repair.

We started doing more indoor work, and remodel work, and started hiring people out of the mission here that were homeless.

When you don't have anything, you really see a different side of a person that are trying to change their lives to get back to some kind of normality.

I try and live my life and operate my business every day to not only help the people that work with me, but the people I work for.

- When I got out of jail and I kind of had that spark, we found this program with a Colorado Coalition for the Homeless.

It was like, "Aahhh.

"” I don't know, the doors and the flowers were growing, and the Sun was shining, and I was like, "This is my moment.

This is where I'm supposed to be and this is what I'm supposed to be doing.

"” That's when my heart started pounding to want to do more.

I was participating on all these committees.

The mayor appointed me to housing people experiencing homelessness committee, a proposal was being put forward to take care of our unhoused community members during a global health crisis.

My boss, he wanted somebody that had been there, had done that, and recovered from it to run it.

I'm so grateful that that was his mission.

There's something very powerful about that moment.

When you can connect with somebody, the walls fall down immediately, and they trust you.

Inherently, you get this.

Yeah, I've been there.

I know what this feels like.

I might not know your exact experience, but I know what you're feeling inside, and it's that power of connection that we lead with in our spaces.

- People that work here and volunteer, they're just like me.

They used to be out there recovering.

They want to give back.

They understand.

I am at the point where I am moving into housing.

I've got my voucher.

Yay!

My number one goal is to reconnect with my daughters emotionally.

When I get my housing, they'll be here with me, and we'll get through it together.

That's all that I want to do is just move forward and show my daughters that no matter what happens to you, you gotta be strong, you gotta fight.

Homelessness is a solvable problem.

I'll say that again.

Homelessness is a solvable problem.

- Housing does work when paired with the appropriate services that that individual needs.

We call that housing first, and we know that housing first works here in our state.

86 percent of people who receive supportive housing are ultimately successful.

That is by far the most effective strategy in reducing and ending homelessness.

- The City of Denver in particular is one of the most cohesive and collaborative cities in the nation.

Throughout Covid, we really proved that that collaborative effort really can make a big difference, and I believe that in 2023 and beyond, we'll be able to make a big dent in what we're seeing, which seems almost insurmountable, but it's not.

We can do this, and we will do this, and I have absolute confidence that that will happen.

- I think as we come out of a time when there was so much isolation, I really look forward to us reengaging in community, and I think that reengaging in community is good for kids, it's good for youth, it's good for adults, it's good for families, it's good for individuals, it's good for people with substance misuse issues, or mental health, or physical health, and I think we've become siloed, and we're slowly coming back together, and we're carrying the scars of that isolation, but I think that's where the real change can begin to happen.

- I can't promise that no one will have an experience of homelessness, but what good looks like is that we have as many people in a month that come into a housing crisis as we have exit that housing crisis.

It is not without difficulty, expense, or time, but it can be done, and we need to do more of it.

This is doable, but we need to do it together.

[Music]

Support for PBS provided by:

Decode Colorado is a local public television program presented by PBS12